Special Exhibition at the Whanki Museum

Whanki

심상의 풍경: 생각하라, 뭔지 모르는 것을…

Landscapes of the Mind: Always Think. of What You Do Not Know…

The special exhibition Whanki, Landscapes of the Mind: Always Think of What You Do Not Know (hereafter Landscapes of the Mind), held at the main building of the Whanki Museum, sheds light on the life and artistic journey of KIM Whanki (1913–1974), with a focus on his New York period (1963–1974).

New York, the city where Whanki pursued his artistic vision until the end of his life, became the place where his search for the essence of nature evolved into a most pristine and complete form of abstraction. The changing seasons, the boundlessness of nature, the warmth of human connection, the quiet decay of his aging body, and a longing for his homeland—these deeply layered emotions etched themselves into his heart and, eventually, into his art. The myriad reflections he recorded in his diaries became the seedbed of a profound creative exploration that traversed figuration and abstraction, culminating in the “Landscapes of the Mind”

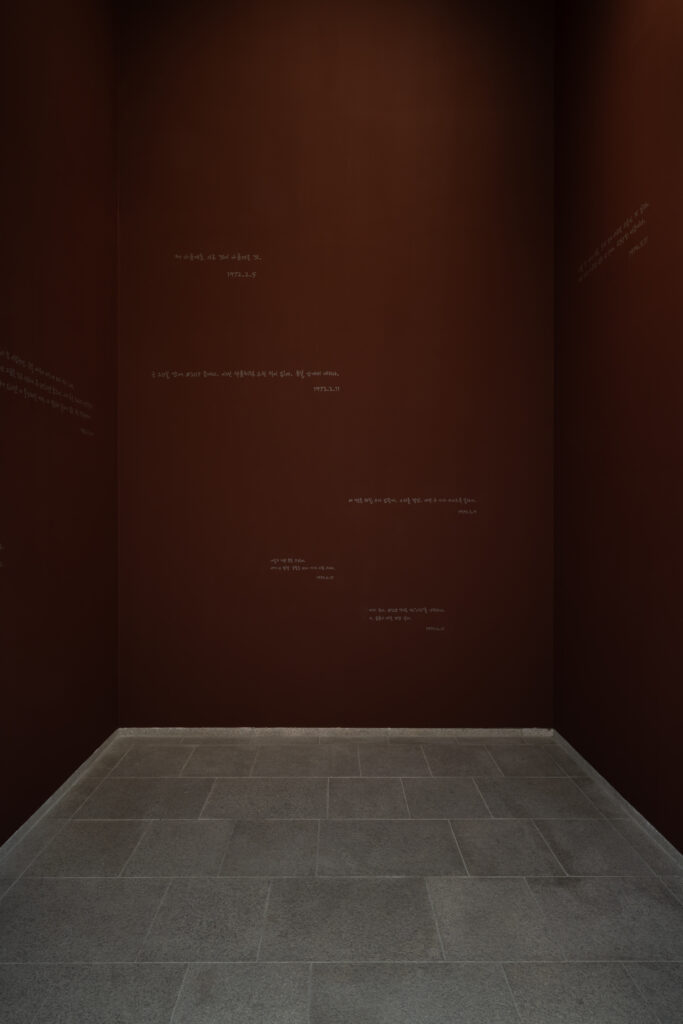

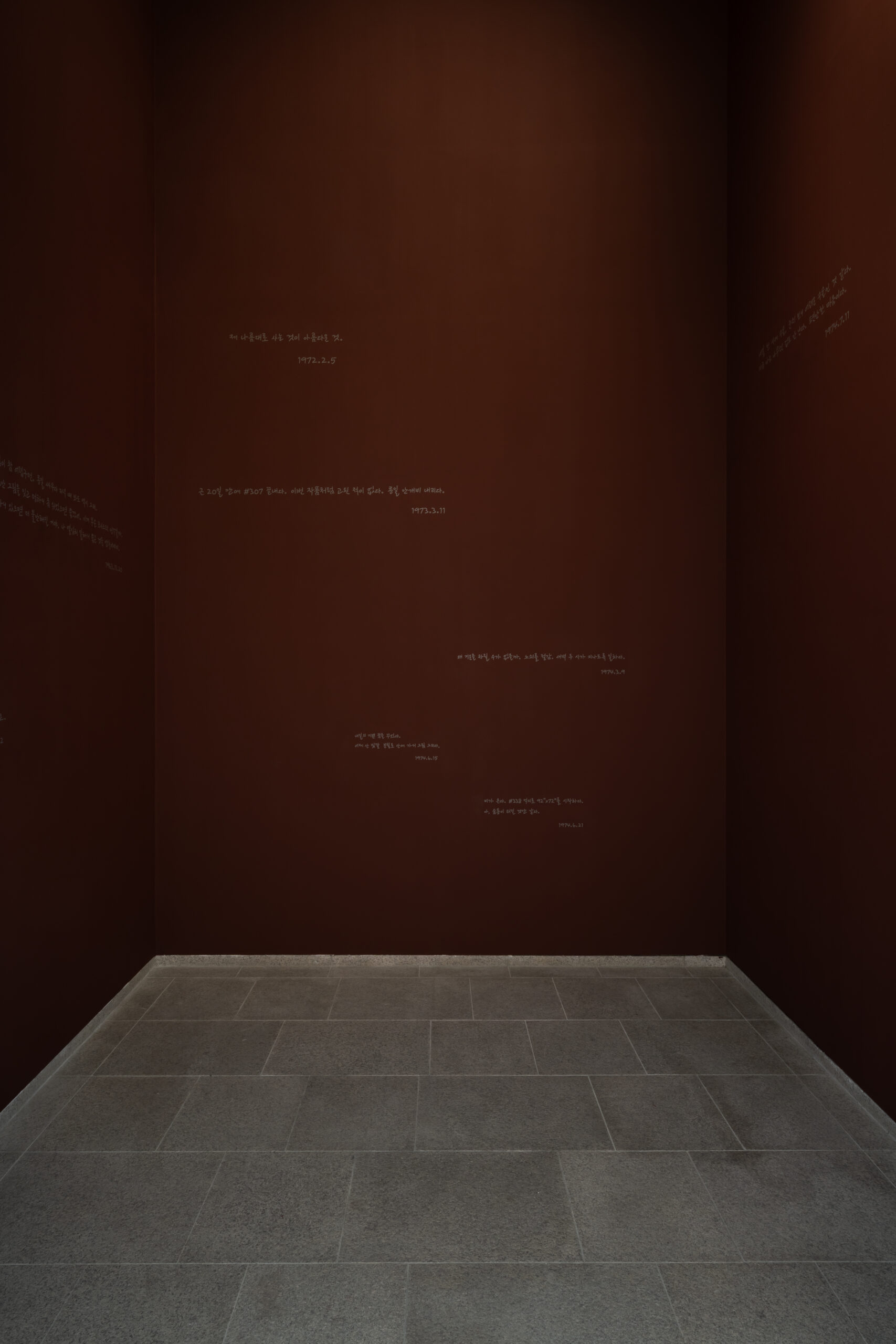

This exhibition highlights KIM Whanki’s abstract paintings alongside his personal writings and reflections—his words becoming a bridge to his creative world. Central to this is his poetic, artistic temperament found in “letter drawings” and diary entries from his New York years, which trace the footsteps of a restless, determined artist. As he once wrote, “Always Think. of What You Do Not Know” (1969). Through that mantra, the hazy fragments of thought he encountered in life transformed into the simplest, purest elements of form: dot, line, plane, and color. These became the foundation of a deeply personal visual language that still resonates today.

KIM Whanki’s New York Period

Whanki lived through a century of upheaval. Born under Japanese colonial rule, he witnessed the joy of Korea’s liberation, only to be displaced by the outbreak of the Korean War, forced to flee south to Busan. Yet amid these trials, Whanki nurtured a dream—to become an artist who could capture beauty and to stand on the world stage as a Korean artist. He had unwavering belief in himself.

One night during the Korean War, writing under the glow of an oil lamp, he sent a letter to his friend, architect Kim Chung-up in Paris: “Korea is a goldmine of art. I believe the future of global art lies in Korea—not just for us, but for the entire world.” (1953) In the midst of war, he and his fellow artists clung to their brushes, and in this struggle, Whanki found faith in Korean art and its potential. He also expressed, in the letter, his hopes for his own artistic world as he set his sights on Paris. Thus, Whanki finally reached Paris—a city he had once only dreamt of visiting—and yet, his heart was drawn once again, this time toward New York, the great crucible of art.

In 1963, representing Korea at the 7th São Paulo Biennial, Whanki traveled to Brazil. There, inspired by the dynamic currents of modern art, Whanki resolved to test and affirm his artistic vision on a larger, global stage. With that decision, he boarded a plane bound for New York, America. Despite being in his 50s—a time when many might have settled into comfort—Whanki left behind status and recognition in Korea to start again in a city pulsing with ambition and creativity. To Whanki, however, New York’s skyscrapers were dry and emotionless. Disenchanted with the modern world, he often longed for home—for the house in Seogyo-dong overlooking the river, for the taste of chueotang (loach soup) by the ferry dock and the simple joy of buying yeot (taffy) when he had a few coins in his pocket. He painted with these memories in his heart and wrote letters to his loved ones.

For the last little while I have been looking either at my picture or at the view out of the window. It must be dawn now in Seoul. Out of the window I can see the cars going past in four lanes in both directions at intervals of about five metres, in geometrical order. Our age is really not an exciting one to live in. How can we make our lives interesting? Last year at this time we liked to look from our place at the river Sokang and its little island of Bansum. Near the landing-stage there was an inn where they served loach soup. We either walked back down by Shinsuk-dong or took the bus. When we had a little money with us we bought barley sugar to eat at home. I understand why B. and K. stayed in Korea so long.

KIM Whanki, November 21, 1963

After arriving in New York, Whanki began working in a corner of B’s studio, a connection from his days in Korea. He longed to create truly great works. He painted in a way reminiscent of his practice in Seoul and often sketched in nearby parks. One day, he met a painter named Raymond, who was fascinated by the cosmic quality and mysterious color of Whanki’s small-scale art works. Encouraged by this rare recognition, Whanki poured his passion into his work.

Yesterday, as I was felling rather nervy, I went out to get some air. I met by chance a painter called Raymond. As he seemed surprised by my sketchbook, I asked him whether what I was doing was to asiatic. He said No, that my small works were very original, giving an impression of universality, with subtle colours. When I meet people like him who show a sincere interest in my work, I feel happy and encouraged. For the Present, instead of producing too much, I am going to concentrate on four or five pictures.

KIM Whanki, December 11, 1963

In 1964, his wife, KIM Hyang-An, joined him in New York, and he was selected for the Rockefeller III Fund’s Asian-American cultural exchange program. He moved into the Sherman Square Studio, held his 17th solo exhibition at Asia House Gallery, presenting around 30 works. These included three pieces submitted to the 7th São Paulo Biennial, paintings brought from Seoul dating from 1959 to 63—Mountain, Mountain and Moon, A Bird Flying Through the Mountain Valley—as well as new works such as Nocturne, Morning Star, and pieces executed in gouache, the water-based opaque medium. Art circles in New York praised “the delicate hues and mysterious atmosphere” of his layered oil paintings, and lauded “the natural and beautiful world” evoked by his gouache works. The following year, in 1965, he was again invited to participate—this time in the Special Exhibition of the 8th São Paulo Biennial—and continued his vigorous activities with his 18th solo show.

However, New York was not always kind. In 1966, Whanki hosted a gathering that included abstract painter Adolph Gottlieb and others from the art world. Through this, he was introduced to the Tasca Gallery and exhibited 30 oil paintings. But the gallery secretly sold his works without payment, and after two years of delay, set fire to the gallery and vanished. At one point, Whanki and Hyang-an even struggled with basic living expenses, forcing her to take a job. New York, while expanding Whanki’s artistic horizons, also burdened him with isolation and uncertainty. Paradoxically, this duality became the very fuel for his creative spirit.

Creation is always an act of discovery.

If something new turns out to have already been done, it loses meaning.

The search for the never-before-seen brings about the diversity of today’s art.

But only when mystery is imbued with artistry does it gain true value—otherwise, it remains a fleeting trend.

KIM Whanki, 1966

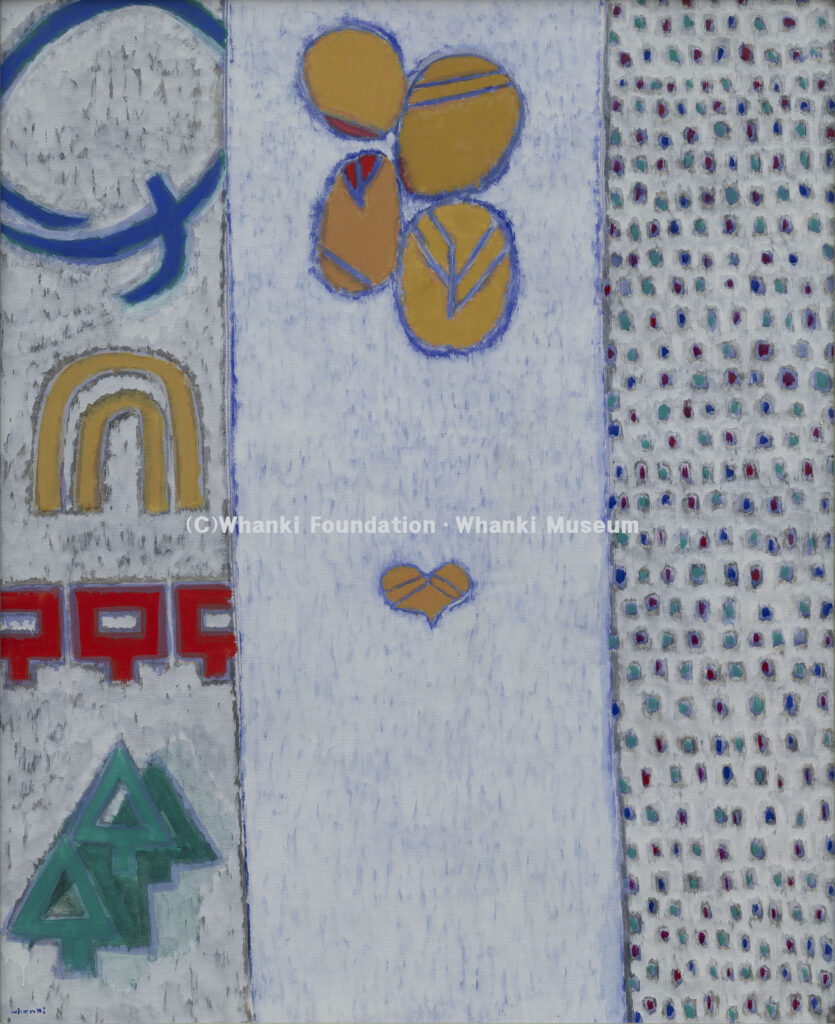

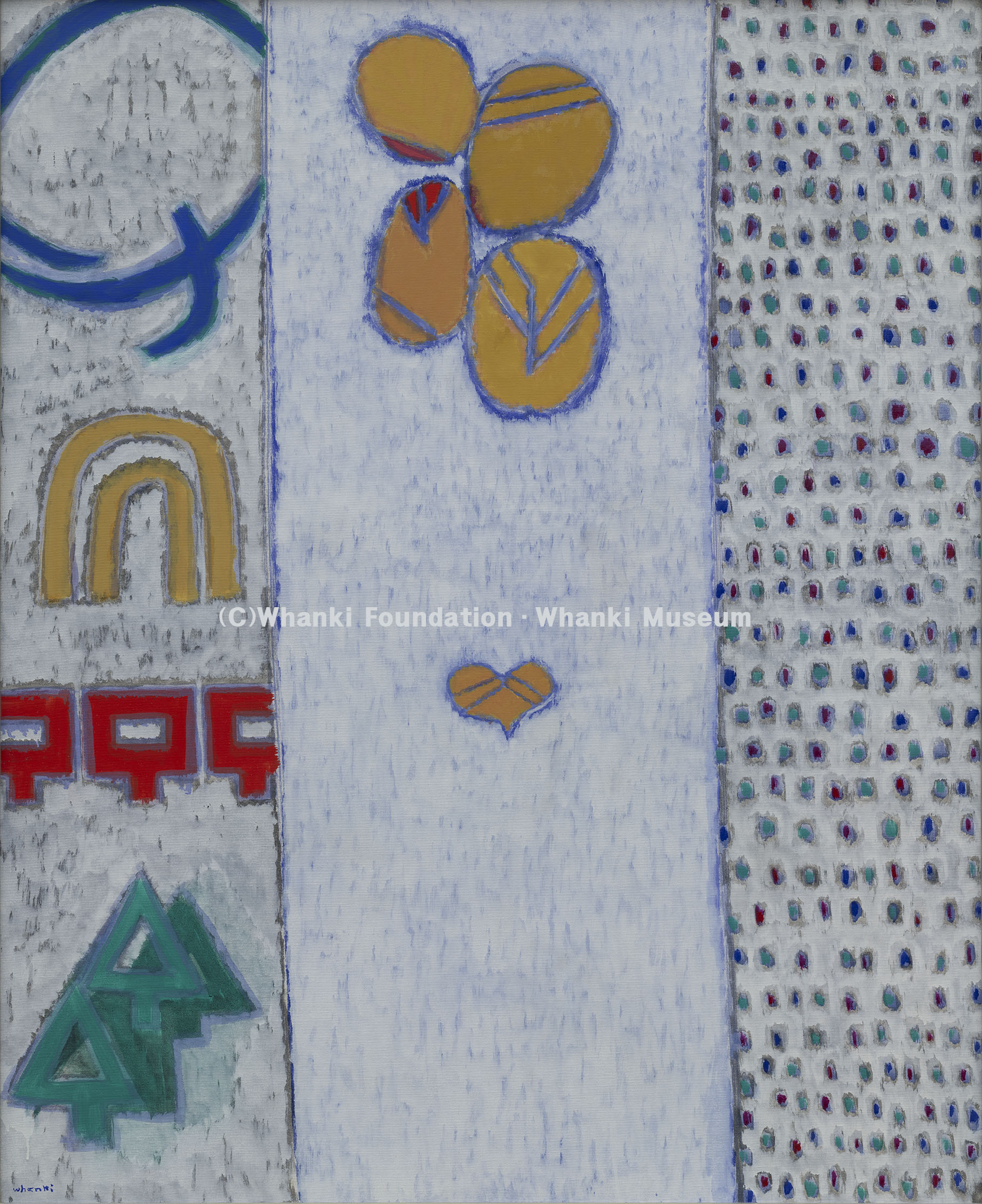

In New York, Whanki boldly explored new compositions and materials, pioneering a unique domain of art that traversed figuration and abstraction. Inspired by nature, his lyrical semiabstract paintings evolved into pure abstract experiments composed of dots, lines, planes, and colors. He painted on a wide range of surfaces—newspapers, packaging paper, hanji (Korean paper), and canvas—and used diverse tools and mediums: knives, Asian and Western brushes, pulp, sand, ink, oils, gouache, markers, and ballpoint pens. From these experiments emerged a vast body of abstract paintings— cross composition, four directional composition, symbolic forms, and pagoda compositions.

Whanki enriched the art world as much as anyone else in the 1960s. He once said, “Art is like venturing into the jungle barefoot. I could die for it and return home with my dream fulfilled.”

In 1970, as he considered returning to Korea, a letter arrived requesting his participation in the inaugural Korean Art Grand Prize Exhibition. Inspired by the poem “In the Evening” by KIM KwangSeop (Lee-San), Whanki completed Where, in What Form, Shall We Meet Again?—a canvas filled with blue dots—and won the Grand Prize. Thus began his late-career masterpiece series: the “dot paintings.” Critics praised this body of work as a realm of lyrical abstraction that exuded cosmic elegance and creative freedom.

Immersed in his dot paintings, Whanki passed away in 1974 at the age of 61. He now rests at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York—a mountain path he often visited.

The richly textured abstraction of his early New York years gradually distilled into pure essence. His use of thinned oil paint allowed layers of color to merge, absorb, and resonate with poetic clarity. As he recalled his distant homeland, he composed a pictorial poetry of dots—a crystallized language of form, a “landscape of the mind” that reached the utmost refinement.

My art is a spatial world. These dots that I am painting as I think of Seoul,

of myriad other things. Could it be that they depict what is inside my mind?

My world of dots…

I have opened up a new window but it seems the new world does not show through. Alas…

KIM Whanki, January 8, 1970