1933-1955

The period of studying in Japan, KIM Whanki, encounters new trends in Western art history. Young KIM Whanki entered the Arts Department of the Nihon University in 1933 and participated in the Avant-Garde Western Art Institute (アヴァンギャルド洋画研究所) in 1934. He had gradually embraced the style of Cubism, Constructivism, and Futurism of western arts trends. Whanki held several prizes and exhibitions at avant-garde art organizations Nika Association (二科会), Hakujitsu Fine Art Association (白日会), Kofukai Art Association (光風会), and Jiyu Bijutsuka Kyokai (自由美術家協会).

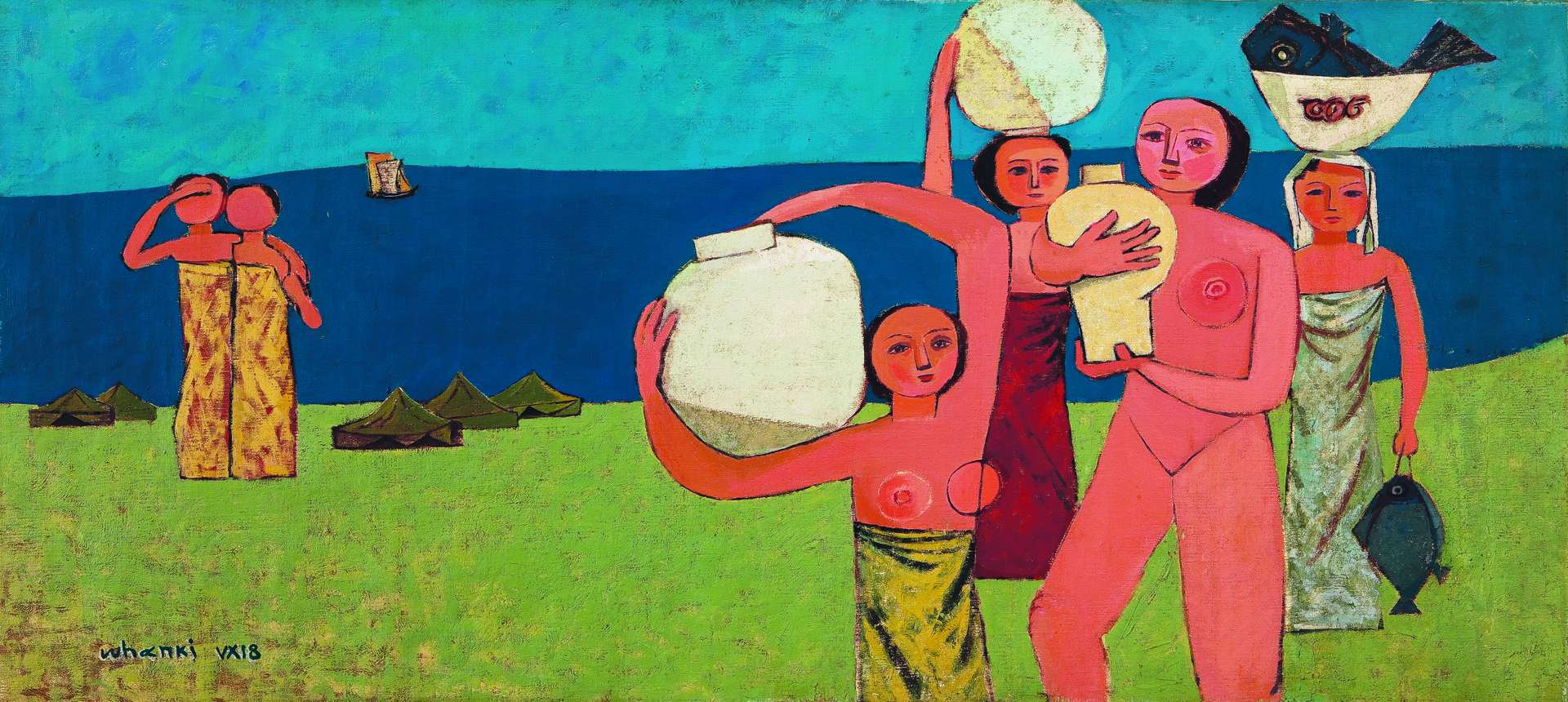

<When the Skylarks Sing (1935)>, a picture filled with a statue of a woman in Hanbok, represents the Tokyo Period. The Woman’s body and arms avoid detailed descriptions and the basket in its head transparently exposes what it contains. The motifs of the picture and the title of the painting are characterized in Korean lyricism, displaying the painter’s bold and experimental expressionist style.

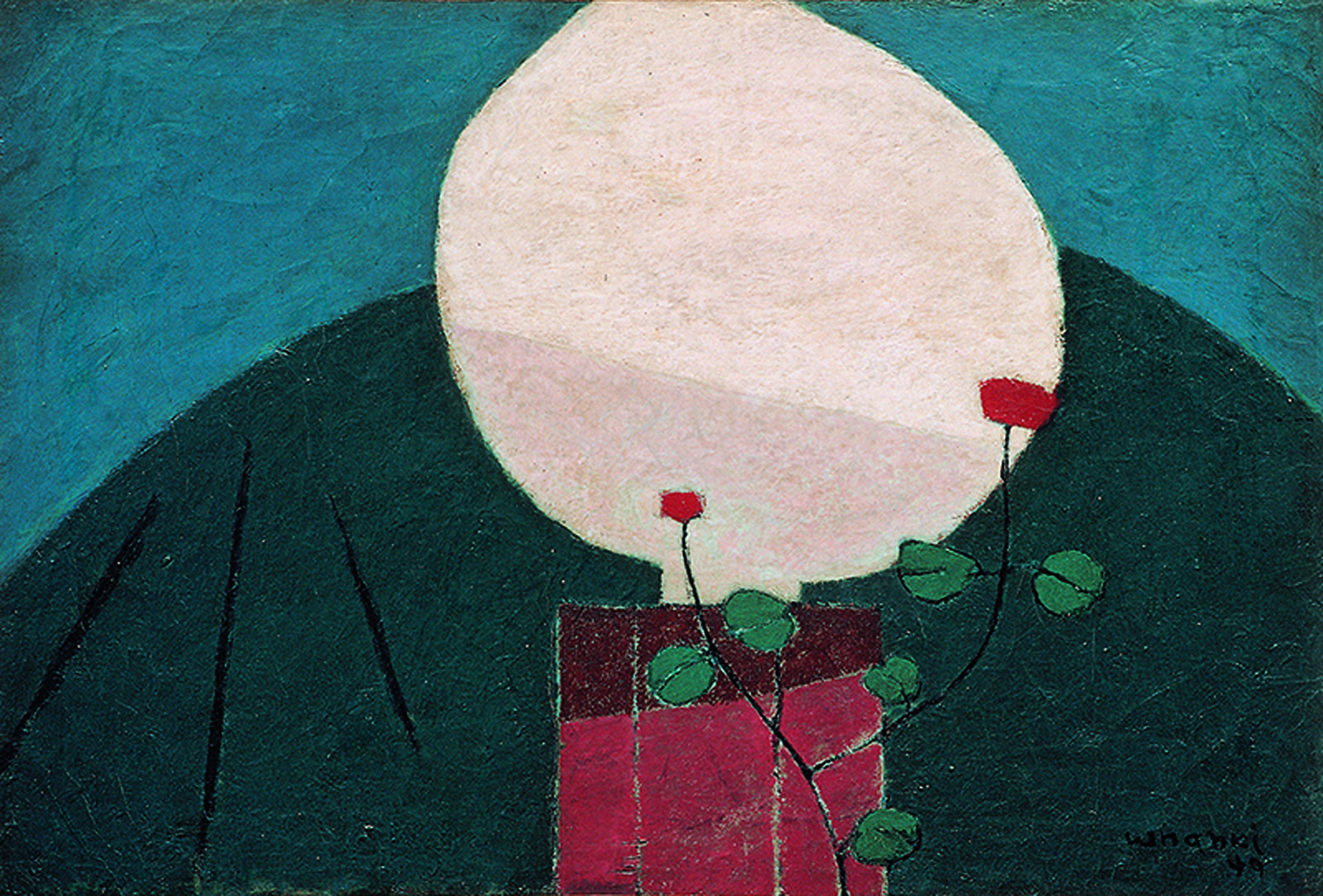

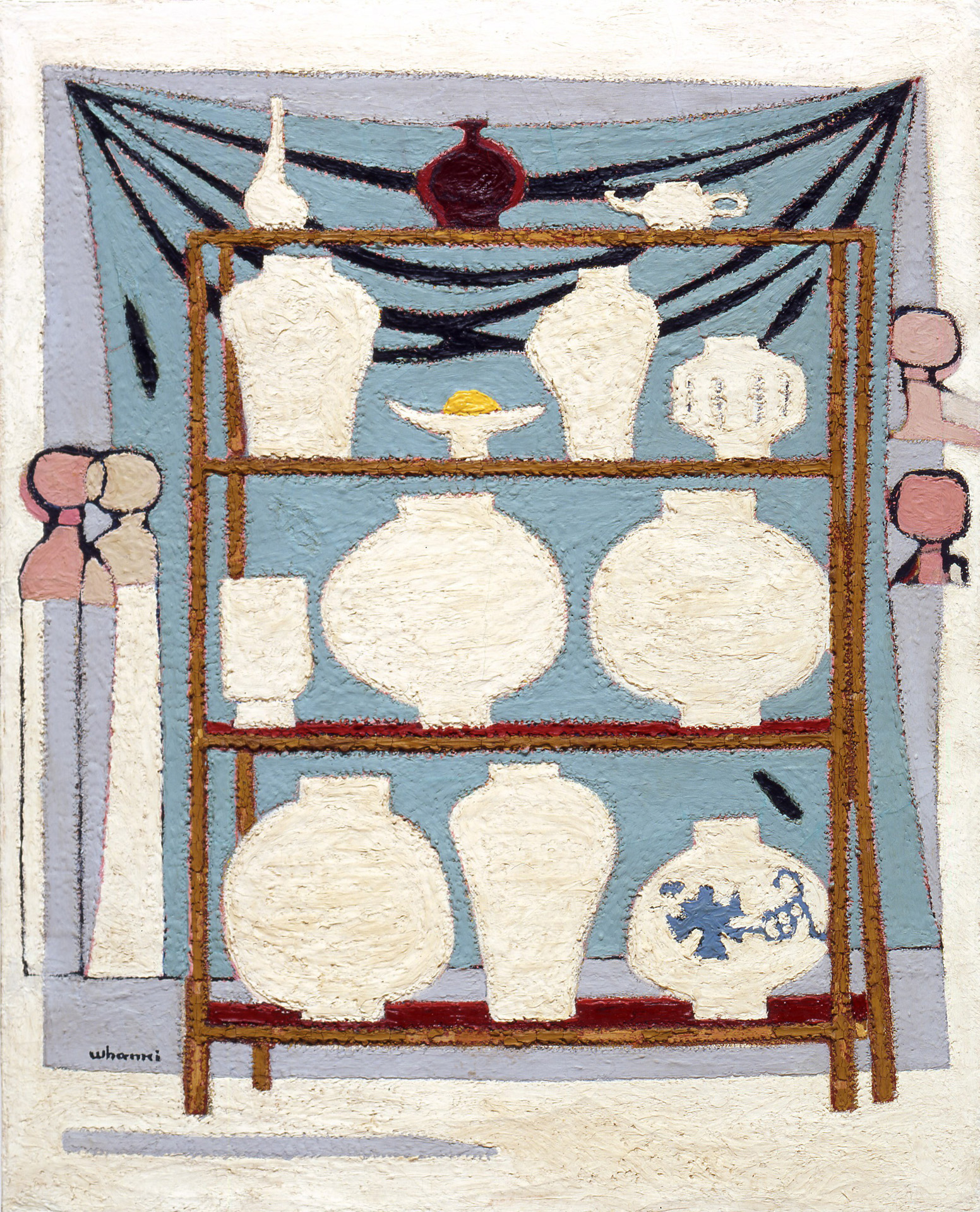

After studying abroad in Japan, Whanki developed a deep affection for national culture and arts, especially in painting the covers and bindings of books, illustrations, exhibition criticism, and collecting antiques. Whanki was particularly fond of and collected the Joseon white porcelain, called “Moon Jar.” He considered that the soft, subtle color, and simple form of white porcelain in the Joseon Period, made with a subtle harmony of soil and glaze, was the best among existing aesthetic values. Since the 1940s, it had been actively expressed as an object for his works.

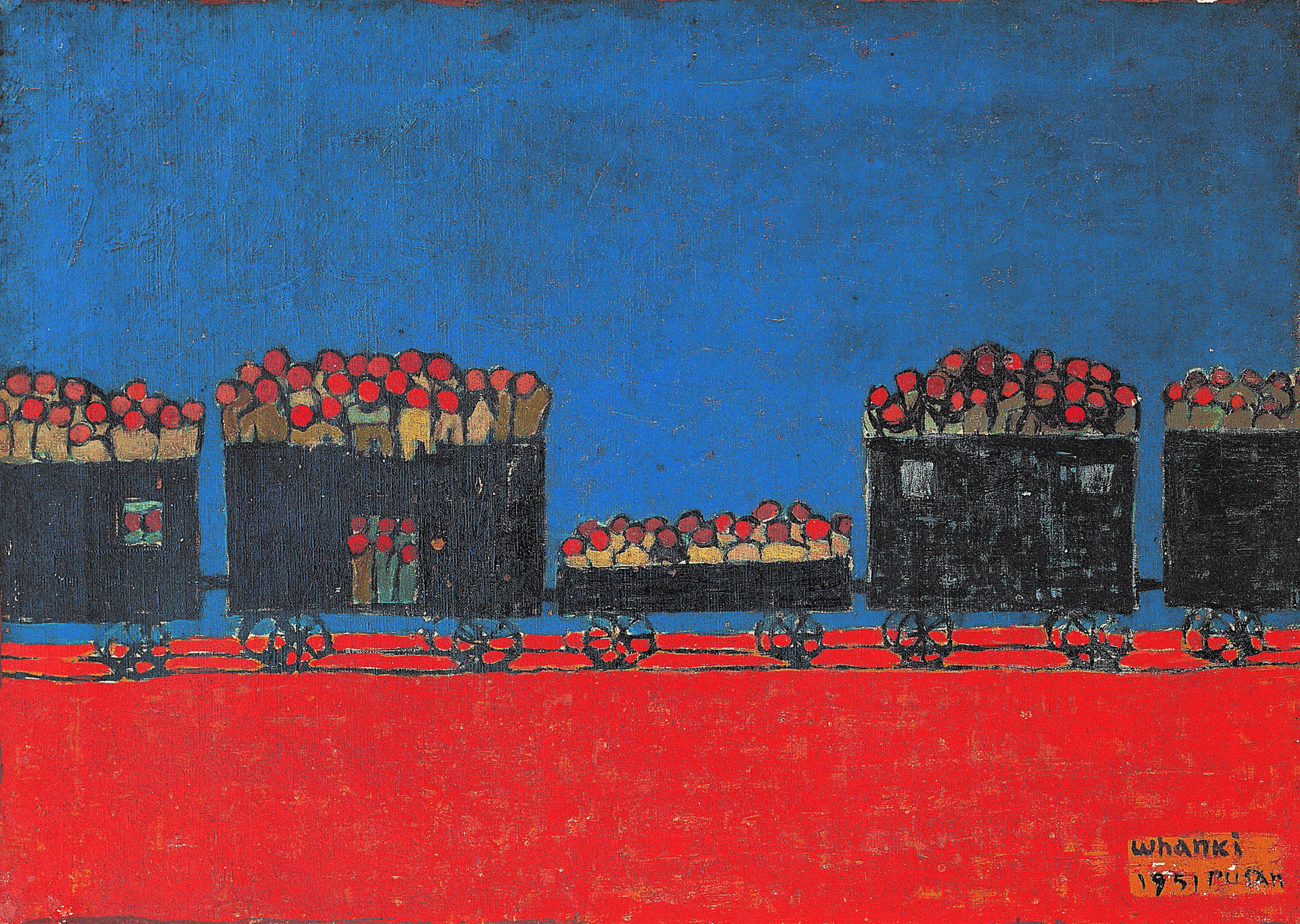

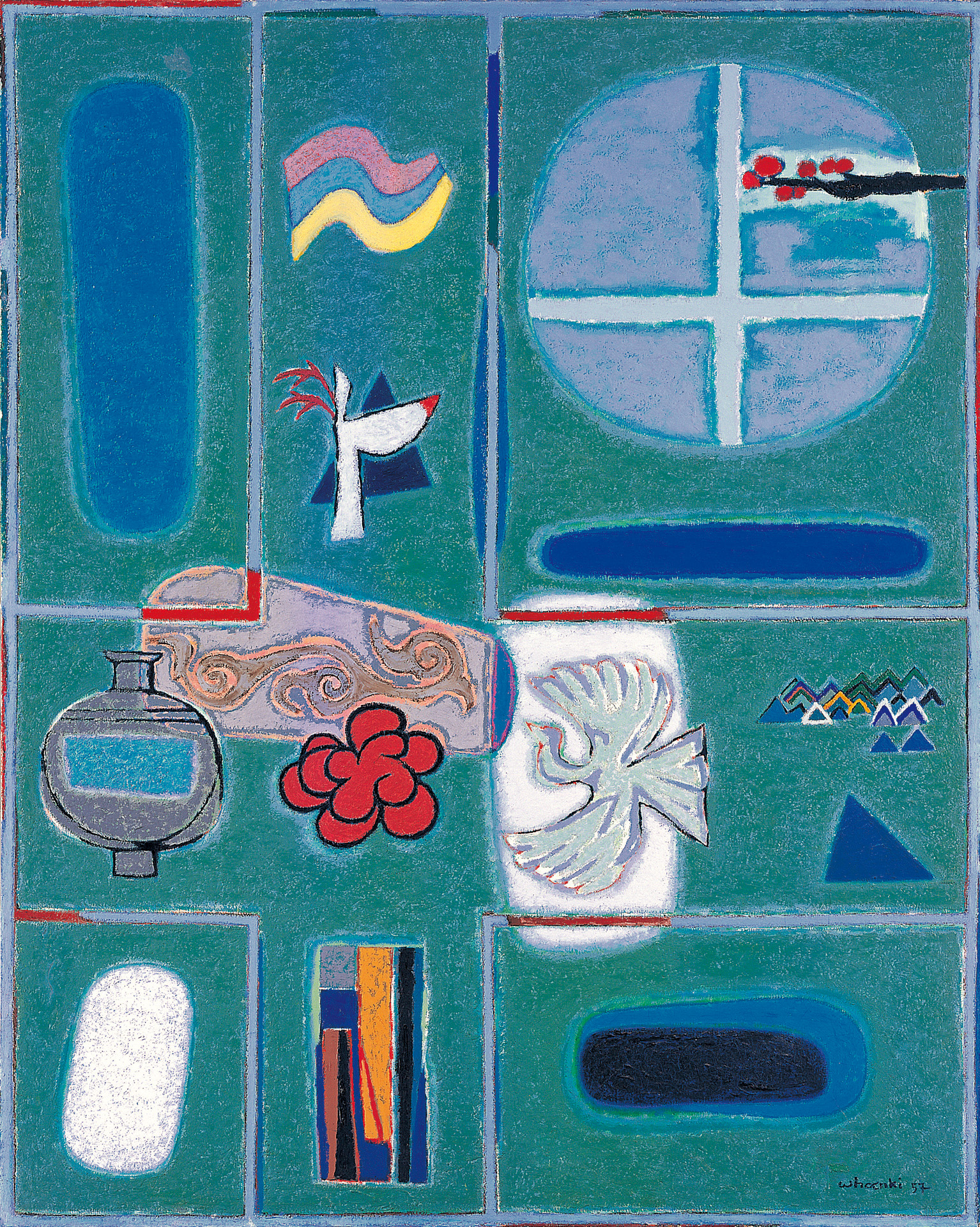

In 1951, Whanki fled to Busan due to the Korean War but did not lose his creative enthusiasm even in the catastrophic period in history. He continued to conceive and publish paintings, writing articles for newspapers and magazines, or sketching scenes of daily life such as scenes of refuges and shantytowns. In addition, he led the Sinsasilpa (New Realism Group), which he formed in 1947, devoted himself to the embodiment of the future of modern art and Korean traditional culture.

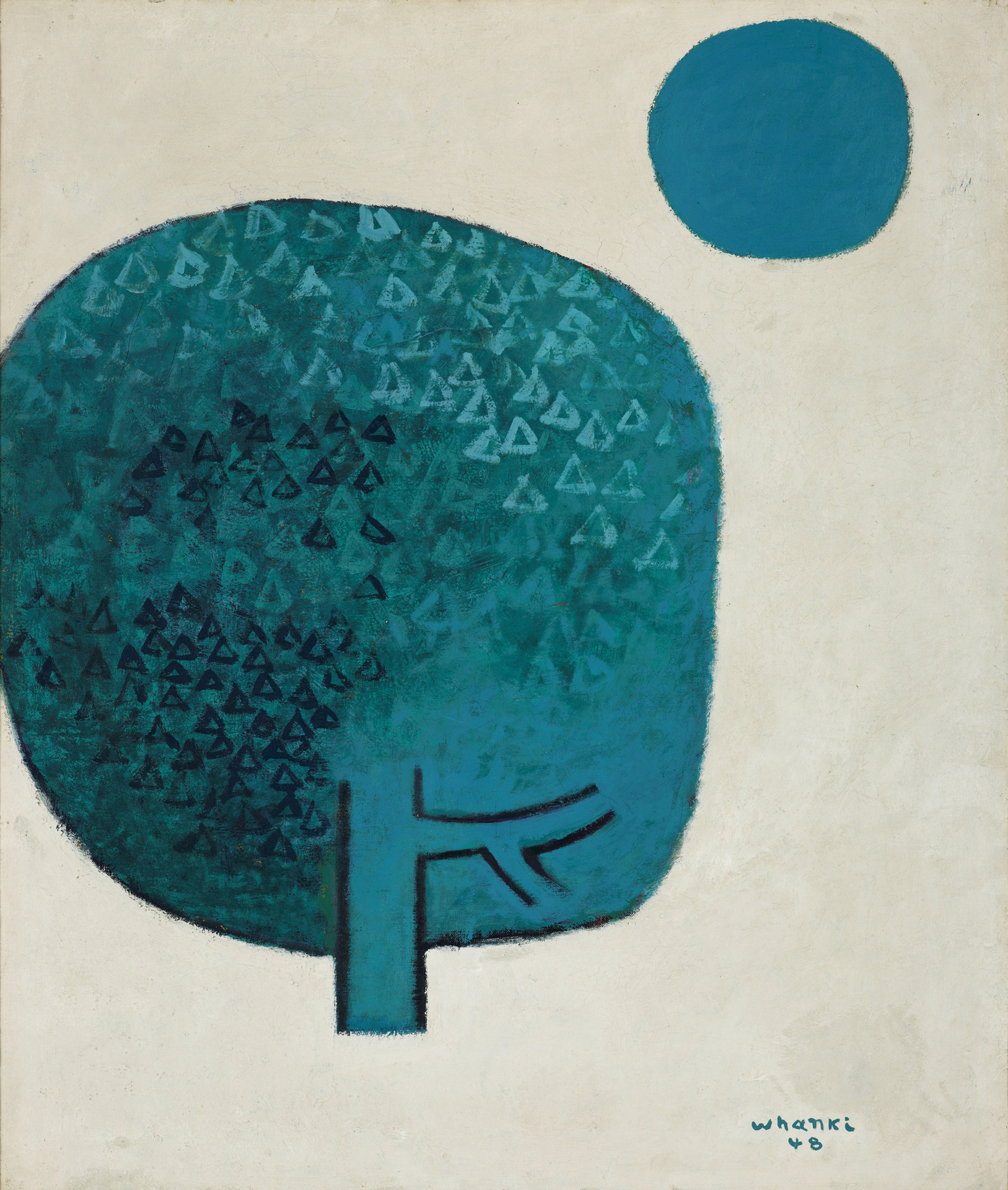

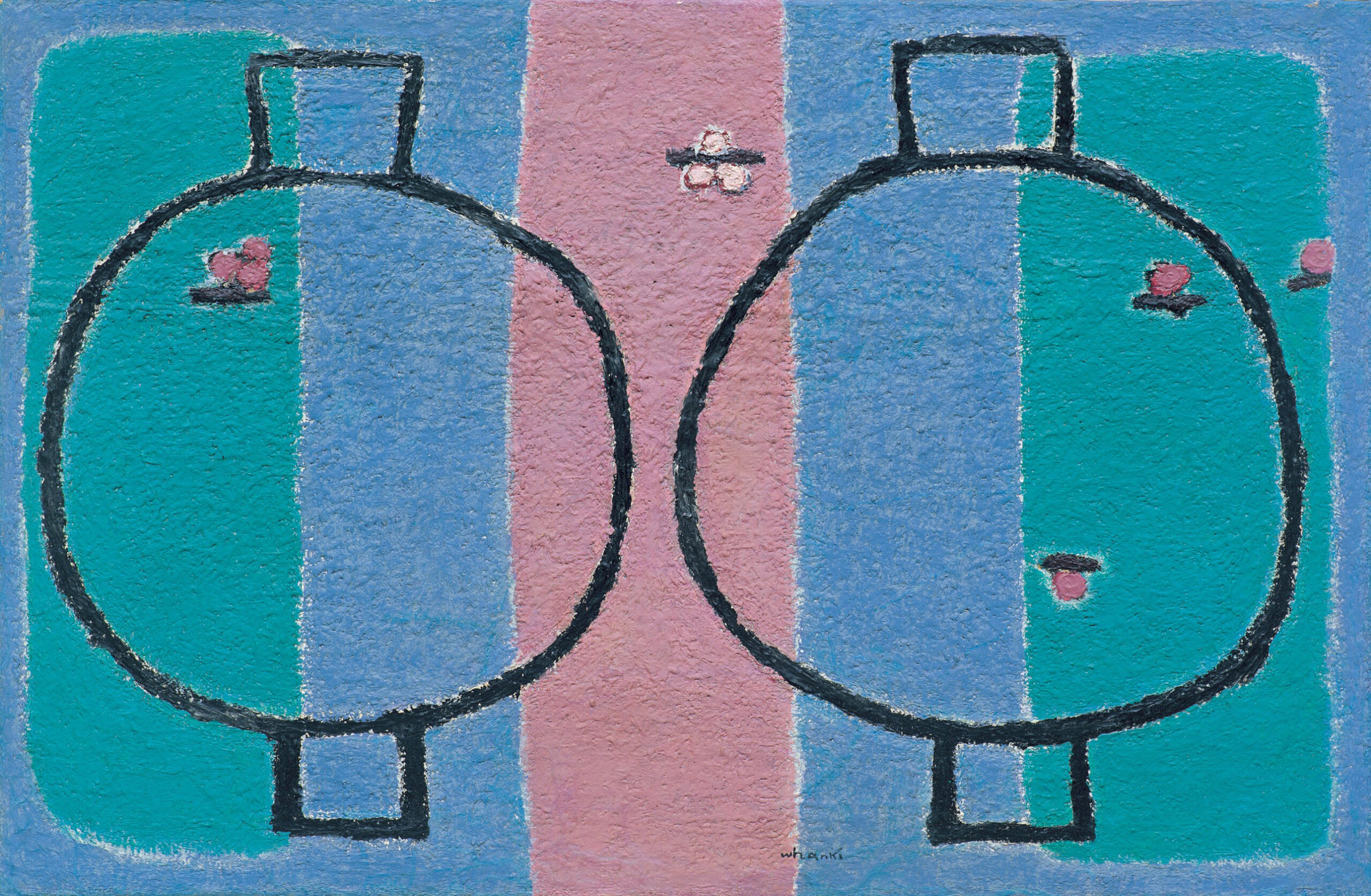

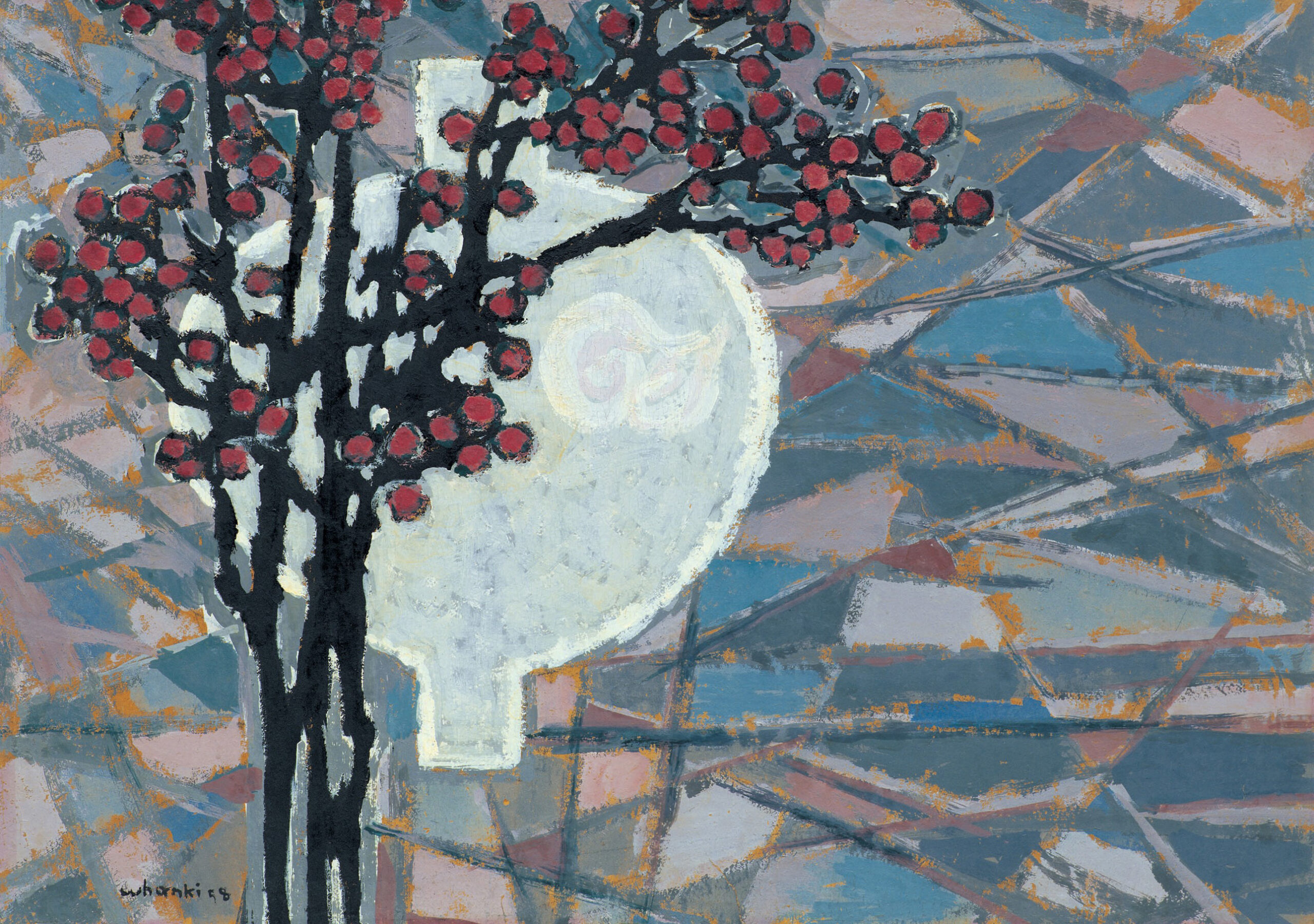

Since then, the extraordinary composition that Whanki showed during the Tokyo Period gradually represented the characteristics of nature and still-life materials resonance of the nature of Korea, such as mountains, the moon, clouds, white porcelain jars, plum blossoms, and many others. During the Seoul to Busan Period, the concise lines of semi-abstract statues were explored the basics of the form that express Korea’s appearance in a thick matière. The artist’s indigenous cultural art and sentiment of Korea started to flow upon the fountain of his art world.

1956-1962

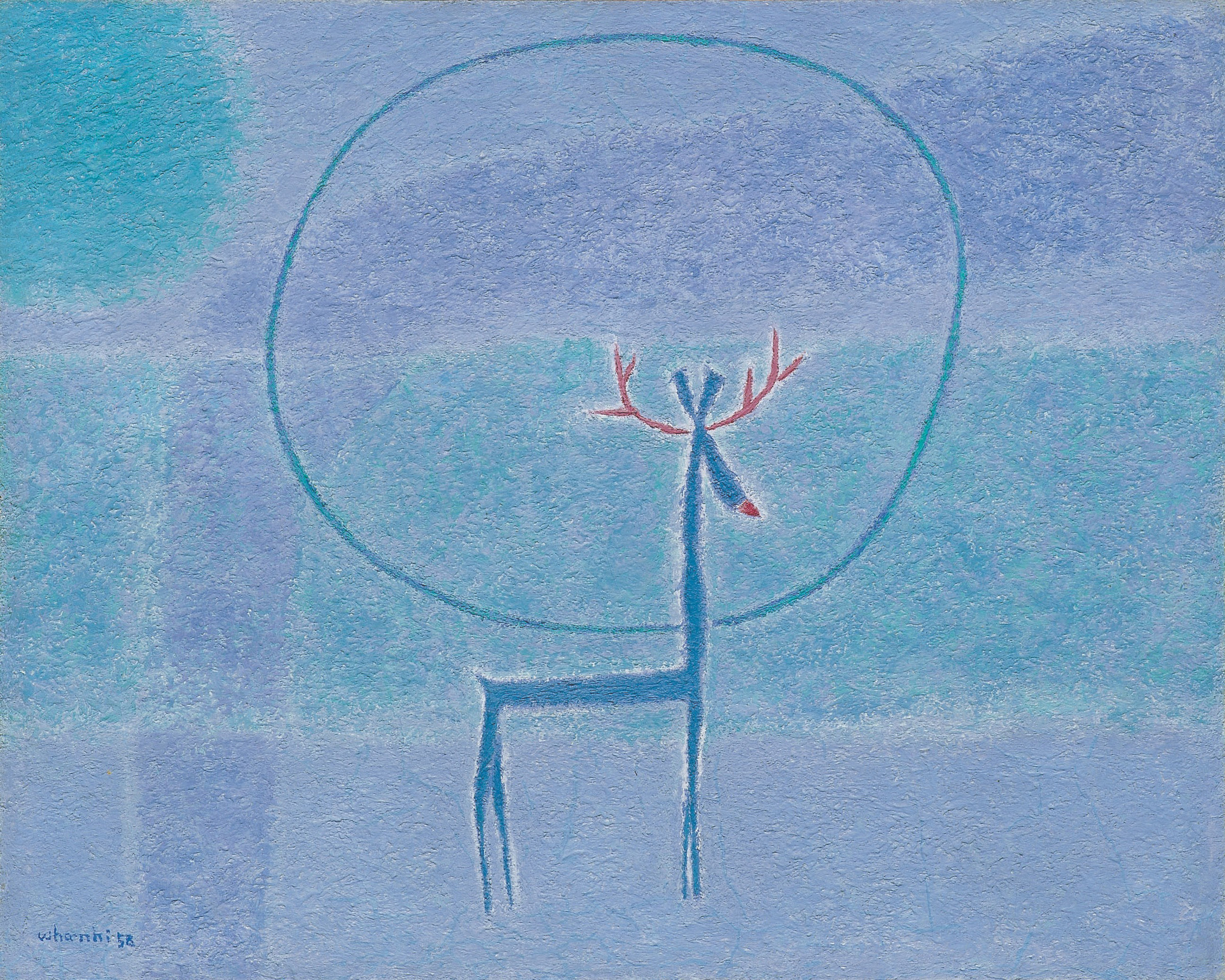

The formative elements that represent Korean nature such as mountains, the moon, deers, plum blossoms, and white porcelain jars are the main objects that appeared in the 1950s works of Whanki.

He had a great attachment to Korean antiques and a passion for collecting it, and which he affected the most was an armful, rounded moon jar in milky and blue-white color. He sometimes placed the jars in the yard, on the cornerstone, and considered them to be as valuable as a living creature beyond an object. A white porcelain jar of Joseon Dynasty was believed to reflect the elegance and dignity of intellectuals of the time. They valued moderation and integrity in thought to see the aesthetics indwelling in nature. The white porcelain jar, a reflection of such nature, sublimated the poetic sense of beauty into the central motif of Whanki’s painting in the 1950s.

As Whanki moved to Paris in 1956, his artistic tendency to seek inspiration through the tradition became deeper and more profound, as the following passage from his journal in January 1957:

[…] I feel the spirit of poetry here

One should hear a song in art.

I hear very powerful songs in many great artworks.

Now I know what I have been singing all these years,

I finally got to know it

as I sensed the bright sun, here in Paris.

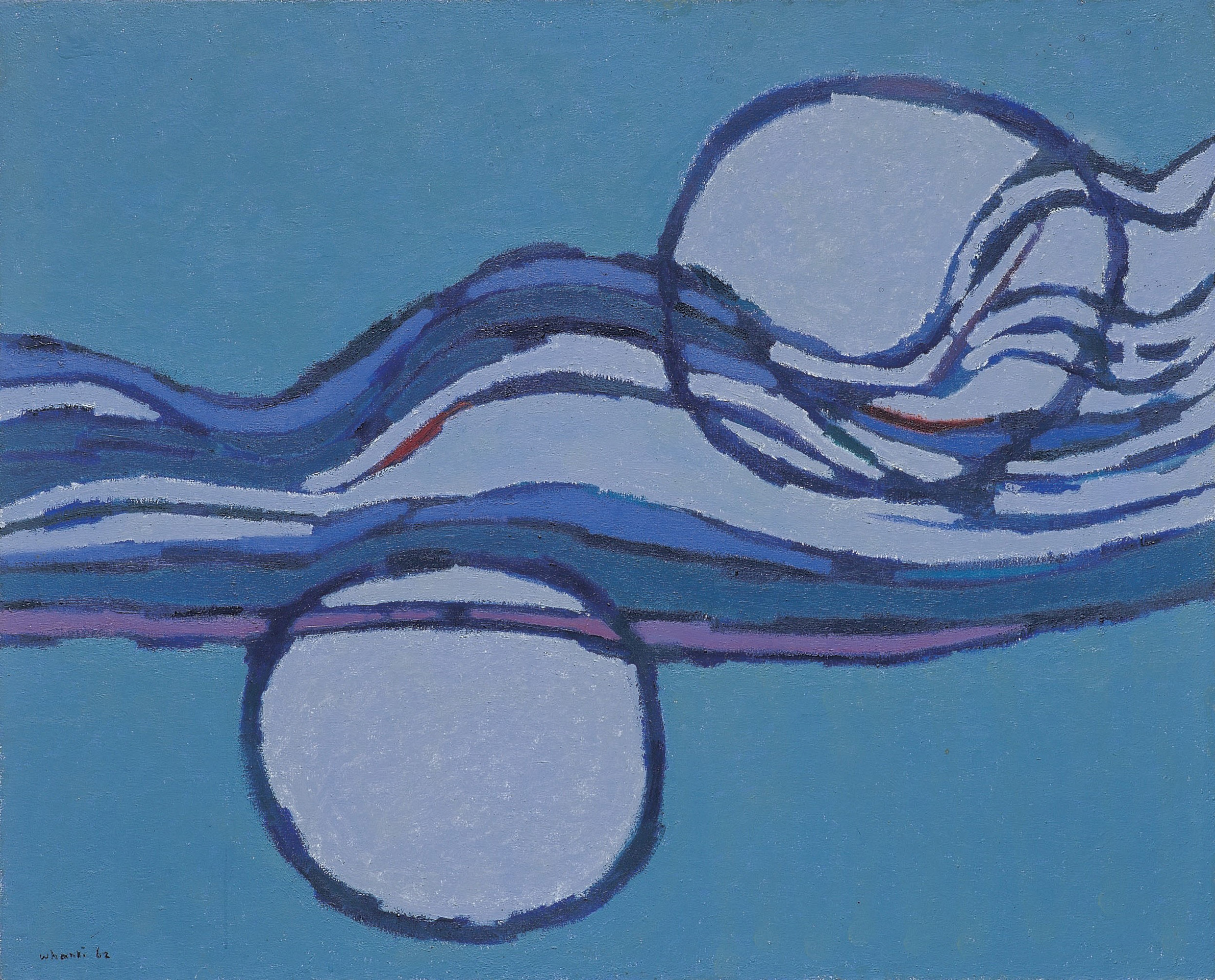

It implies that the artist’s attachment for traditional formative beauty, color, and texture had become more exceptional. In the 1950s, Whanki pursued an overflowing lyrical and poetic formative world with a modern interpretation of the Eastern philosophy to capture the natural order that circulates in the painting. Within the infinite space of the monochrome, the artist embodies the idealistic reflection that he ever dreamt in the form of an universal concept.

During the three years of stay in Paris, he held six solo exhibitions, including in Nice and Brussels, and the material and color experiments were developed and newly represented in the later New York Period.

1963-1974

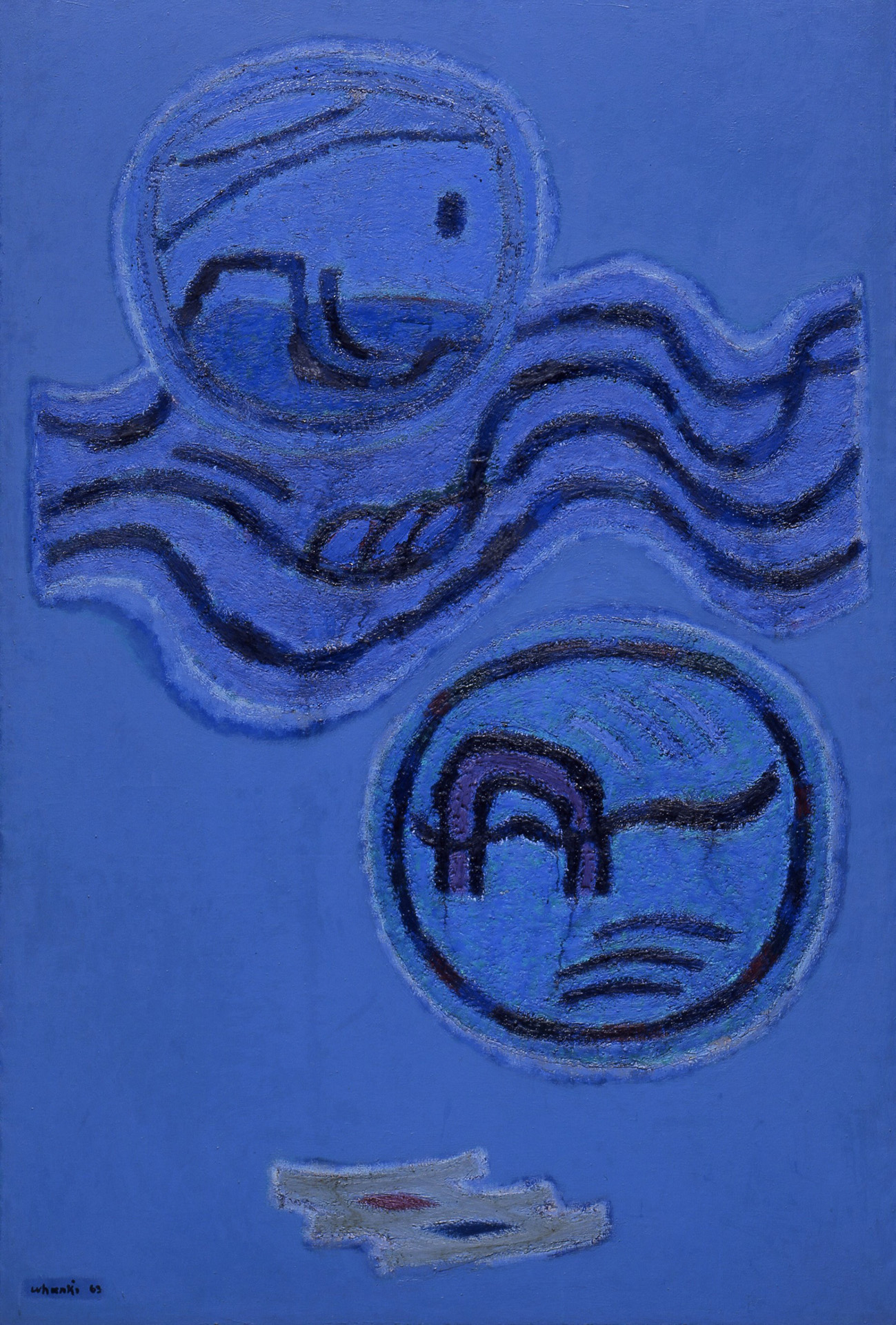

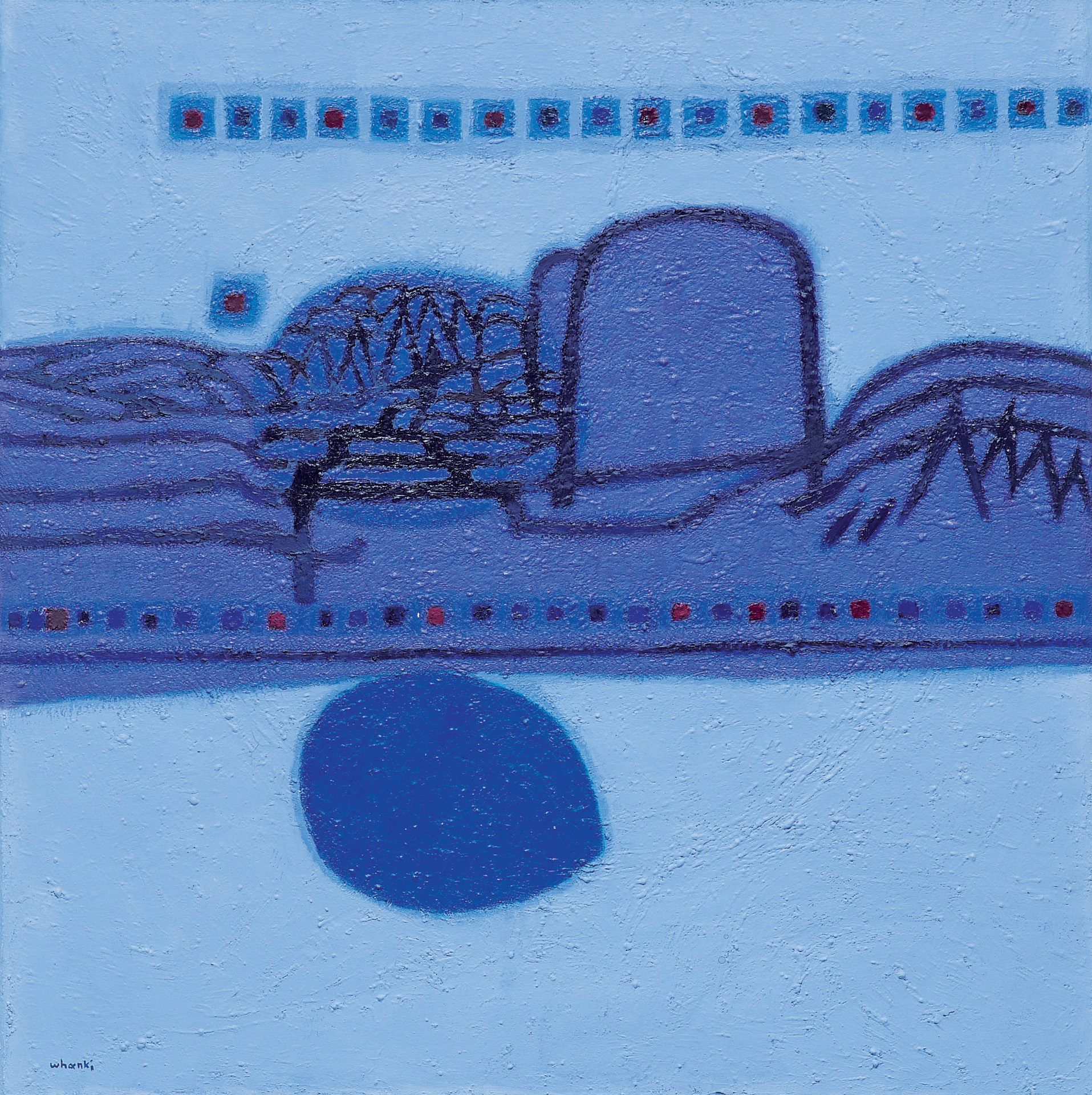

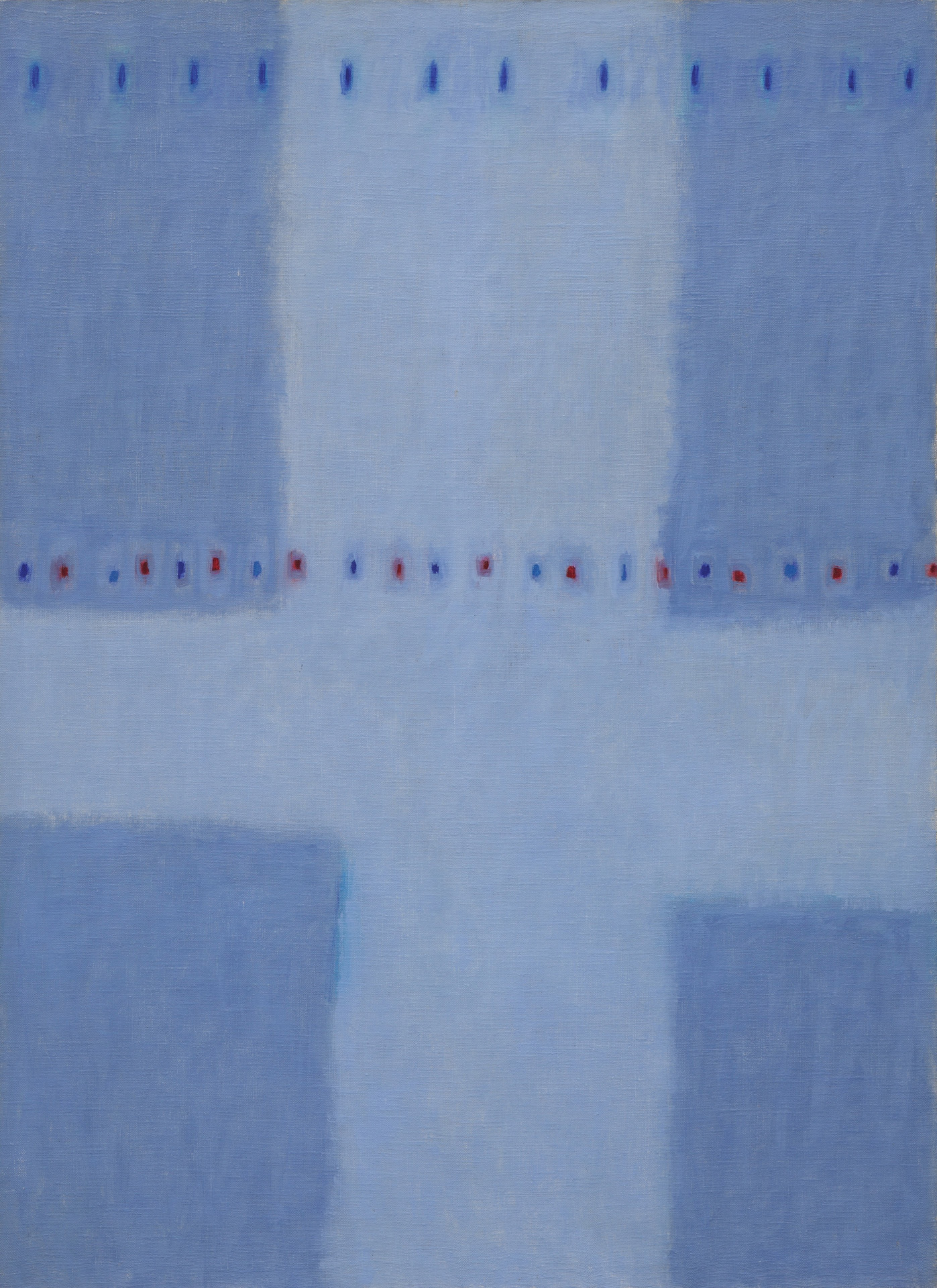

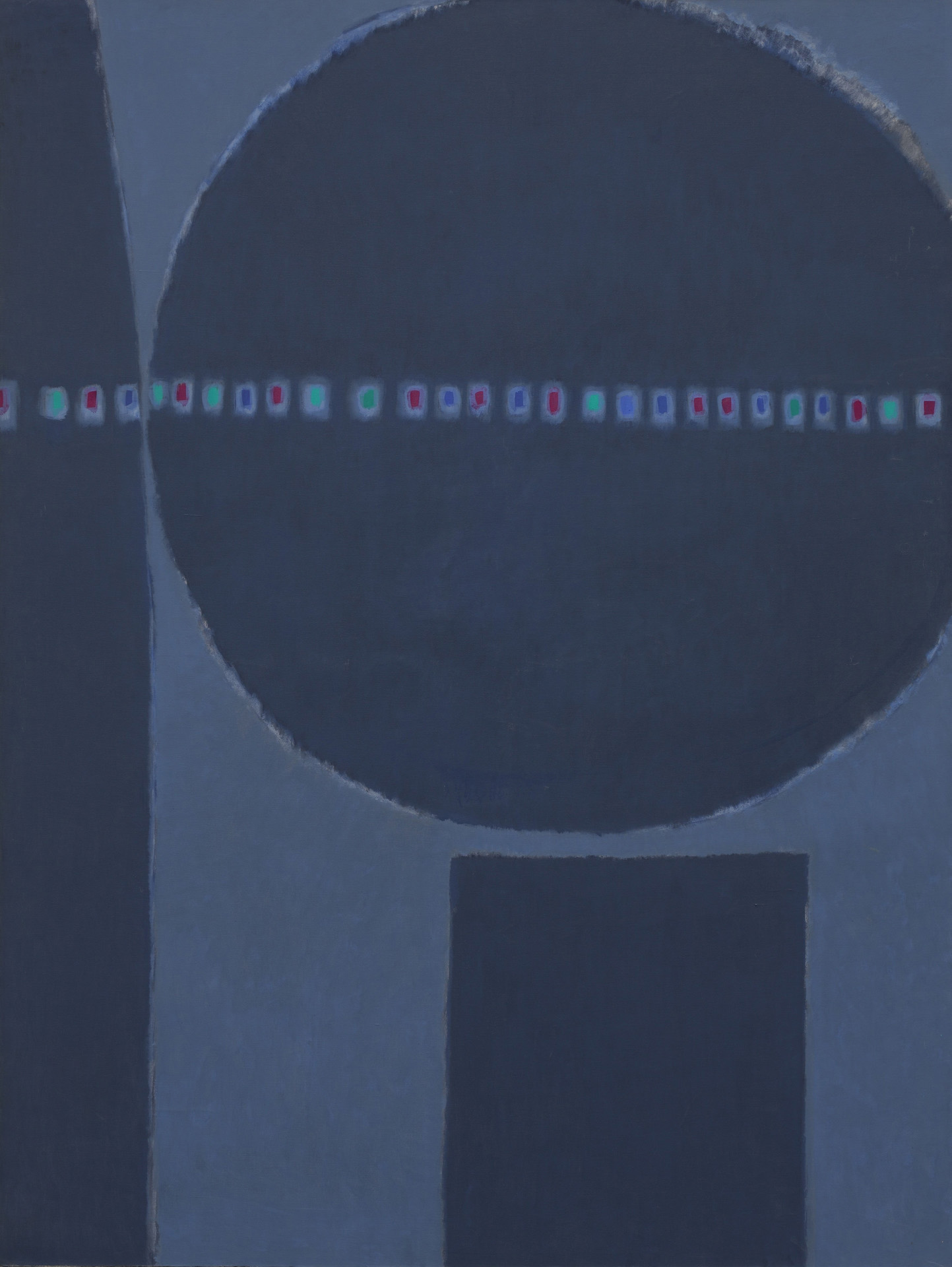

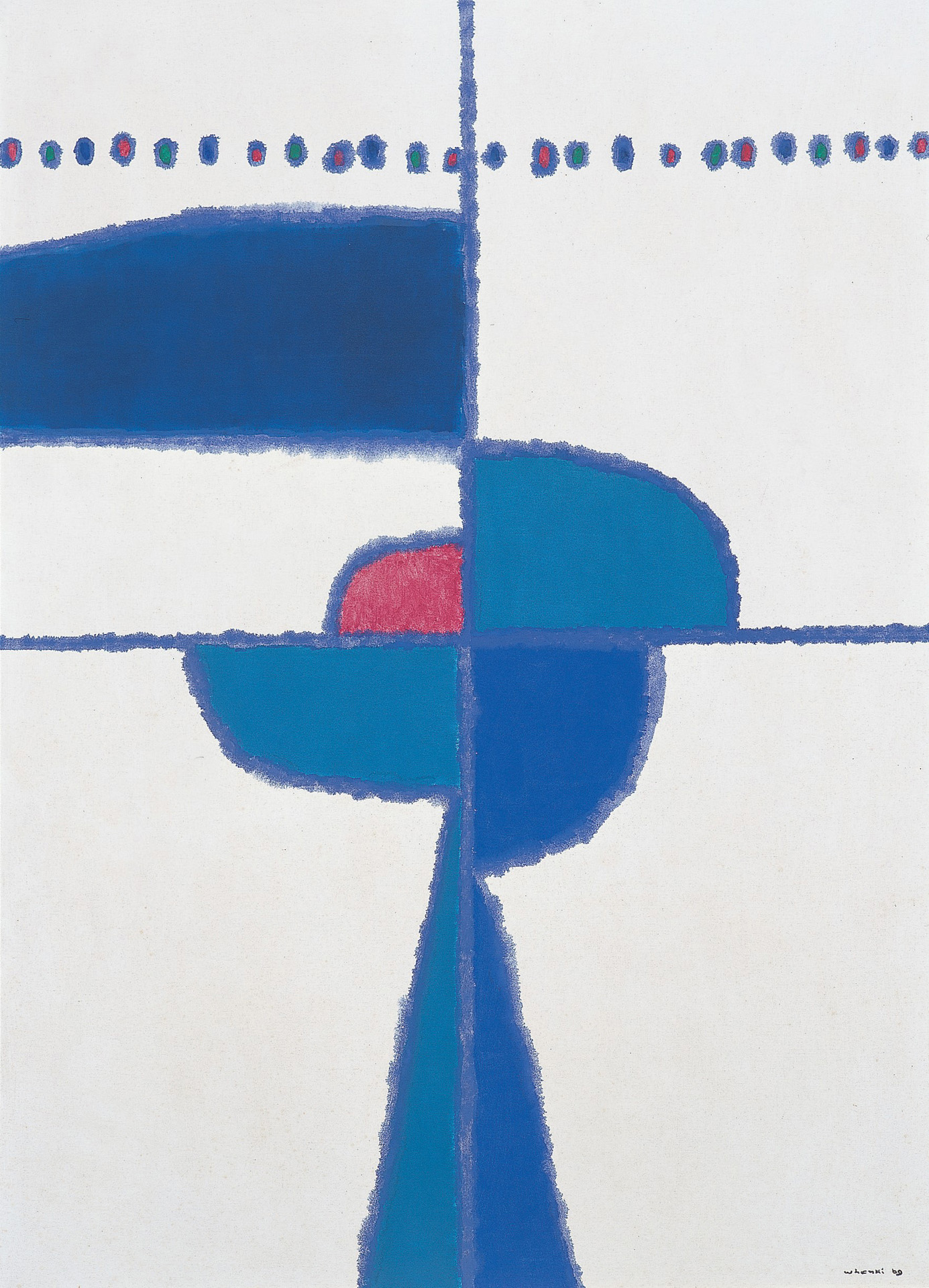

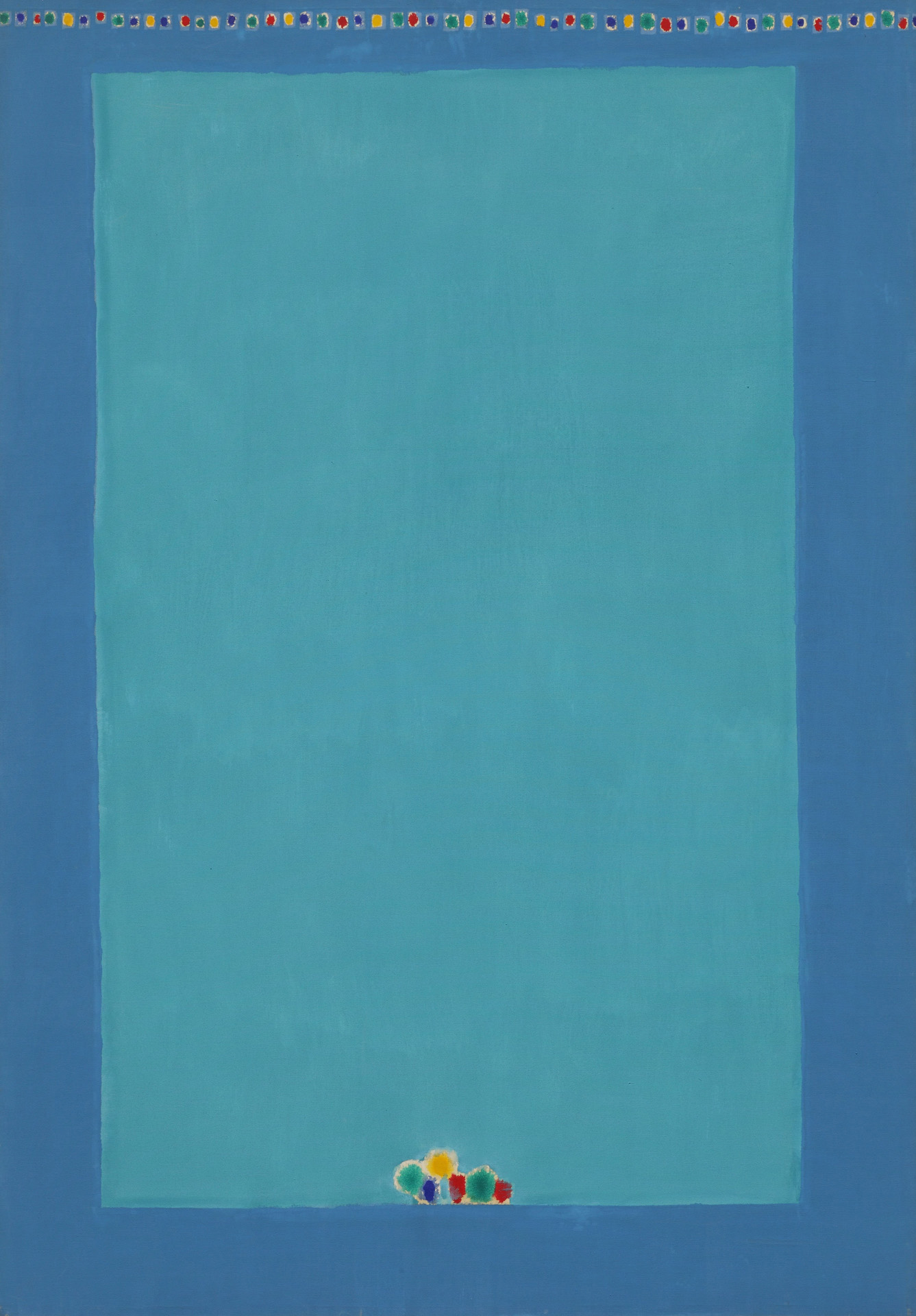

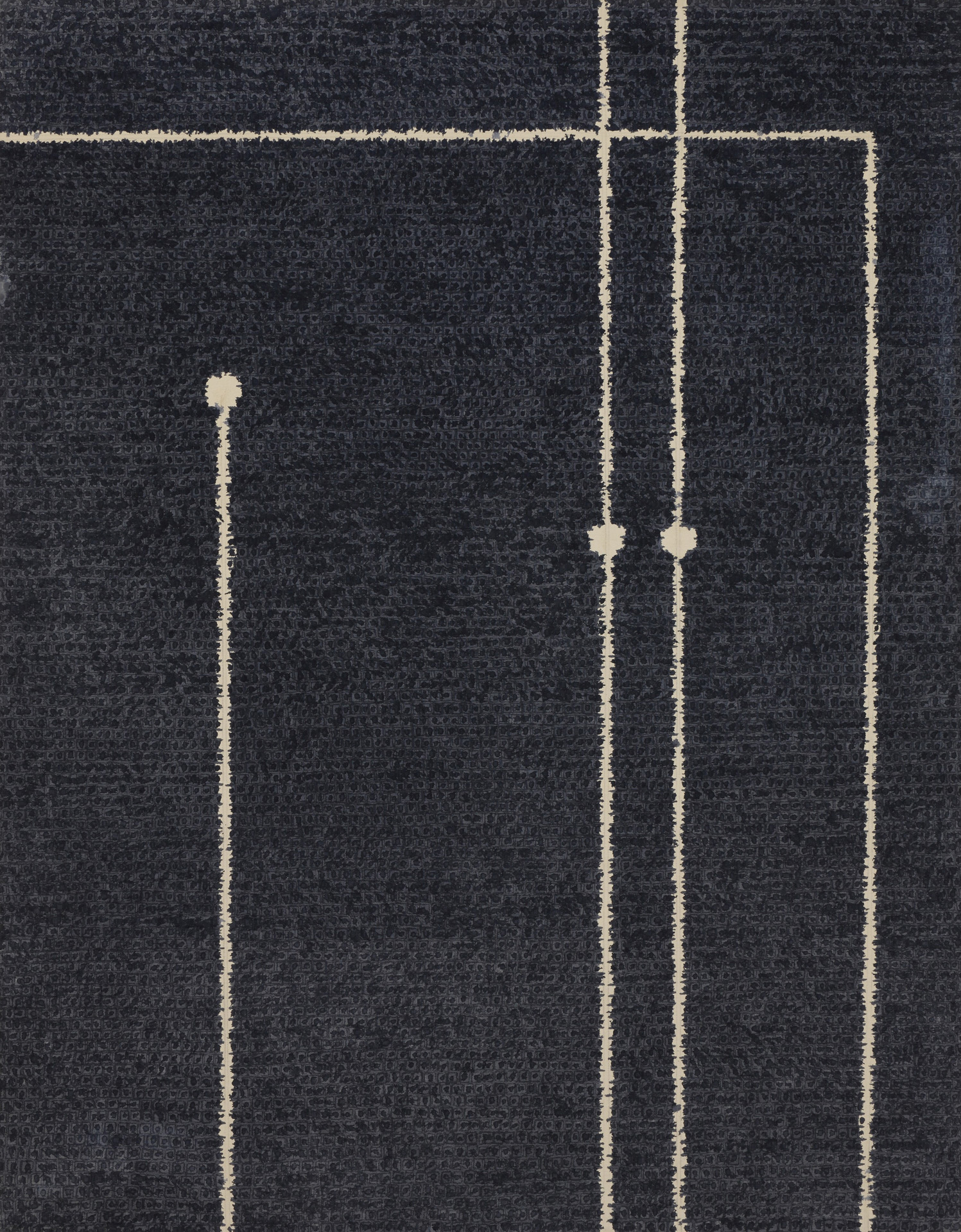

Through the New York Period from 1963 to 1974, the natural landscape with mountains, the moon, birds, and trees atomized into intimate lyricism as dots, lines, and planes.

It was written in the artist’s journal on January 23, 1968: “Trying with flying dots and dots gathered to symbolize shapes.” These dot motifs performed in the New York Period went through various formative research that freely crossed the materials and styles, such as gouaches, collages, papier mȃche, oil on paper, drawings, etc. developed into overall dot painting in the 70s.

One of the well-known dot painting series <Where, in What Form, Shall We Meet Again (1970)>, titled after the verse of poet KIM Kwang-seob, reminds the vast ocean and sky view of Gijwa Island where Whanki was born and raised. His infinitely expanding cosmic space is embodied by brushing lines and dots with oil paint diluted with turpentine on the fine cotton.

The repetition of dots merged into a line, and the lines into a plane, gives the whole perspective as a fused harmony. Dots also smudge and stain on the screen, the individuals creating rich and diverse compositional waves and rhythms. This is not a composition created through a clear sheet of blueprint but an organism born with potential that the uniqueness makes the viewer feel as if the screen is breathing.

The cosmic space painted using deep and mysterious colors such as Cerulean Blue, Ultramarine, Prussian Blue, Rose Red, Rose Madder, whereas the specific image like mountains, the moon, or the sky are no longer there. A poetic formative language are accompanied to the infinite world marking along with the artist’s feelings of joy and sorrow onto each color. Leaving dots was not a casual behavior, but an inscription of the artist’s life in the relationship, nature, and music he had met. Once after reading his friend’s letter, he responded in the forwarding letter saying, “A cuckoo has been crying since early in the morning. Thinking of the cuckoo’s song, I drew blue dots all day long. One said that the barley has ripened on the offshore island. I have a lot on my mind.” His dots were a secret conversation with nature and a world where he lived in and built the fundamental communication into his arts.

Since Whanki moved to New York, his style has turned into a more universal and broader consensus beyond ethnicity. The industrial environment of New York didn’t derive turbulence for the artist who embodies the emotion and affection to nature on the canvas. A nature that he understood was not external being but the principle of creation itself that lives and breathes with him. Through this contemplative gaze, the artist pursued a painting along with sacred-heart, even in the foreign metropolitan, that expresses the purest sense of poetry on nature and infinite cosmic space.